What I mean by “Linux phones”

Before we go deeper, one clarification:

Yes — Android uses a heavily modified Linux kernel and is technically Linux. But the user space, architecture, and development model are so vastly different that Android deserves its own category.

By Linux phones, I mean smartphones that still feel like Linux under the hood:

- You can open a terminal and run familiar commands like

ls,cd, ortop - Graphical interfaces are inspired by desktop environments, adapted for touch and small displays

- Wayland and lightweight compositors are used for rendering

- Most apps are open-source and freely available

This is Linux as a general-purpose operating system — not Linux hidden behind an Android abstraction layer.

A brief history of Linux phones

Years ago, Canonical, the company behind Ubuntu, attempted to build a Linux phone. Significant resources were invested, followed by a Kickstarter campaign — which ultimately failed to reach its goal. Canonical discontinued further development.

Ubuntu Phone, developed by Canonical. Commercially unsuccessful, but foundational — its code lives on today as Ubuntu Touch under the UBports community.

The silver lining: everything they built was open-source.

What was once Ubuntu Touch is now maintained by the community as UBports, under a foundation of the same name.

Canonical wasn’t alone.

One of the most ambitious attempts was MeeGo, a joint effort by Nokia, Intel, and the Linux Foundation. While MeeGo didn’t survive as a consumer platform, its code lived on. The strongest descendant today is Sailfish OS by Jolla — a system that thrives in a small but dedicated niche.

Jolla remains active in its niche. A reminder that not all Linux phone efforts disappeared — some simply chose sustainability over scale, with Sailfish OS evolving quietly in the background.

Another notable player is Purism, which builds the Librem Phone and develops PureOS. One of their long-term visions — desktop and phone convergence — is something I personally care about deeply. I once owned a Microsoft Lumia 950 largely for this reason. That story deserves its own article.

A rare example of a vertically integrated Linux phone. Purism develops both the Librem hardware and its Linux-based operating system in-house — a demanding path that trades mass-market appeal for control, openness, and principled design. Video courtesy of Purism.

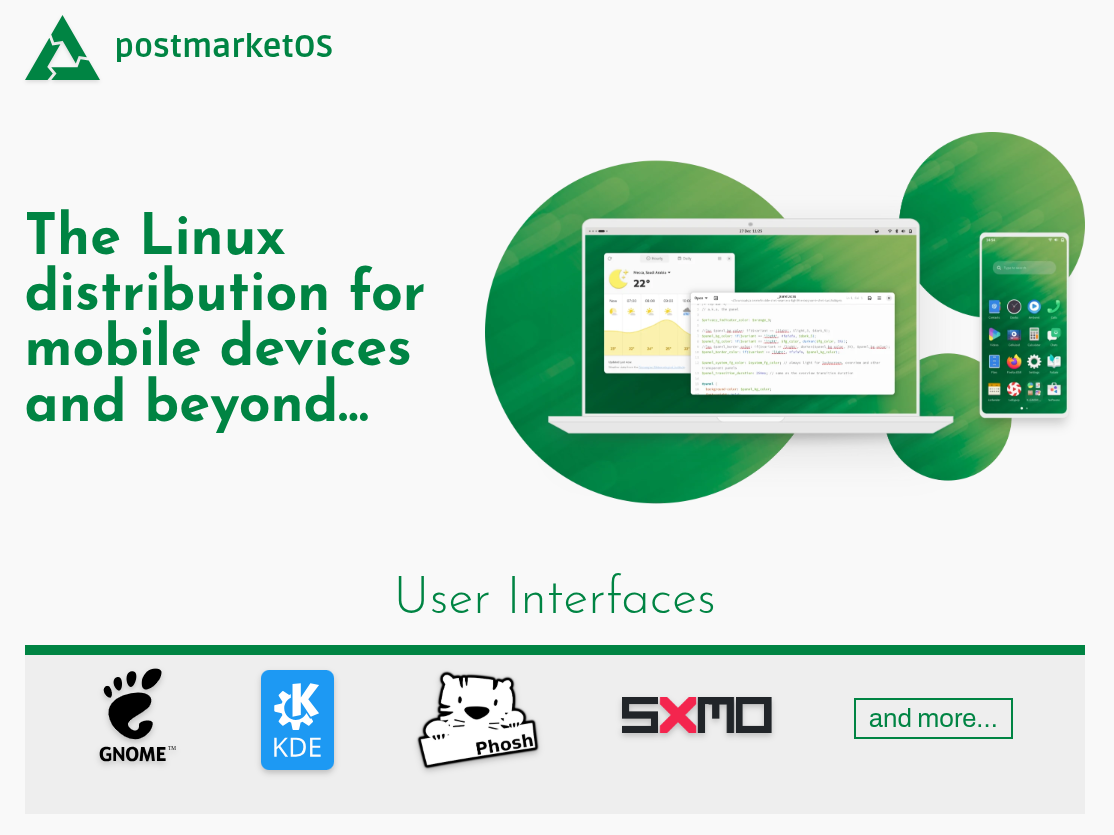

Finally, there is postmarketOS.

Think of it as Arch Linux for phones.

It provides a minimal base system where the entire user space can be swapped:

- one week UBports

- another week Plasma Mobile by KDE

- or something obscure, just because it’s Sunday

The elephants in the room

There are three fundamental blockers that prevent Linux phones from becoming mainstream today.

1. Modems, vendor blobs, and the call problem

Many truly Linux-based phones struggle to reliably make phone calls — not because of Linux itself, but because of closed modem firmware and missing drivers.

Modern smartphones rely heavily on vendor blobs — closed-source firmware components we have no visibility into. The most critical of these is the cellular modem.

If the modem cannot communicate with the operating system, your phone becomes a small computer without cellular connectivity — and sometimes without Wi‑Fi or Bluetooth.

Vendors typically ship drivers only for Android. These drivers are already compiled, closed, and integrated at build time. We cannot inspect or modify their behavior.

The community workaround is Halium.

HAL stands for Hardware Abstraction Layer. Halium reuses Android drivers, communicates with the modem and other components, and translates calls so that a more standardized Linux user space can function.

It’s a pragmatic compromise — not an ideological victory — but it’s the best we have today.

2. Hardware reality

Phones that run Linux natively are scarce — and intentionally underpowered by modern standards.

Think:

- low‑resolution displays

- 2–4 GB of RAM (while modern Android phones ship with up to 16 GB)

- cameras that work, but barely

These devices prioritize openness and hackability over raw performance. They’re excellent for development and experimentation, but difficult to recommend for daily use.

That said, I have a lot of respect for companies like Pine64. I own a PinePhone myself, and my experience with it is very hands‑on.

PinePhone Pro — openness first, polish later. A developer-focused Linux phone designed for experimentation, not mainstream daily use. Official video by PINE64.

3. Apps — or the lack thereof

Microsoft learned this lesson the hard way.

Without popular apps, even a technically solid platform struggles to survive.

As a former Android developer, I know what it takes to ship a polished app. Supporting Android and iOS is already expensive. Adding Windows Phone — or a fragmented Linux ecosystem — rarely makes business sense.

Cross‑platform development promises one codebase for all, but in practice it often sacrifices deep system integration and still requires extensive testing. That’s why even frameworks like Flutter usually target Android and iOS first.

On Linux phones, open‑source apps cover basic needs — but forget mobile payments, biometric authentication, or seamless navigation. Google Maps works via a browser, which limits usability.

One partial solution is Waydroid — running Android apps inside lightweight containers. Support is hit‑or‑miss, but it helps bridge the gap.

It’s the classic chicken‑and‑egg problem.

My relationship with the Linux phone ecosystem

I’ve always been tempted by new things.

I’ve built Android ROMs, experimented with custom kernels, and spent time deep in the weeds. Even so, I draw the line when my phone can’t make a call.

I don’t expect Linux phones to see rapid adoption — if they ever do. But I still believe there is room for a more open alternative to today’s locked‑down platforms.

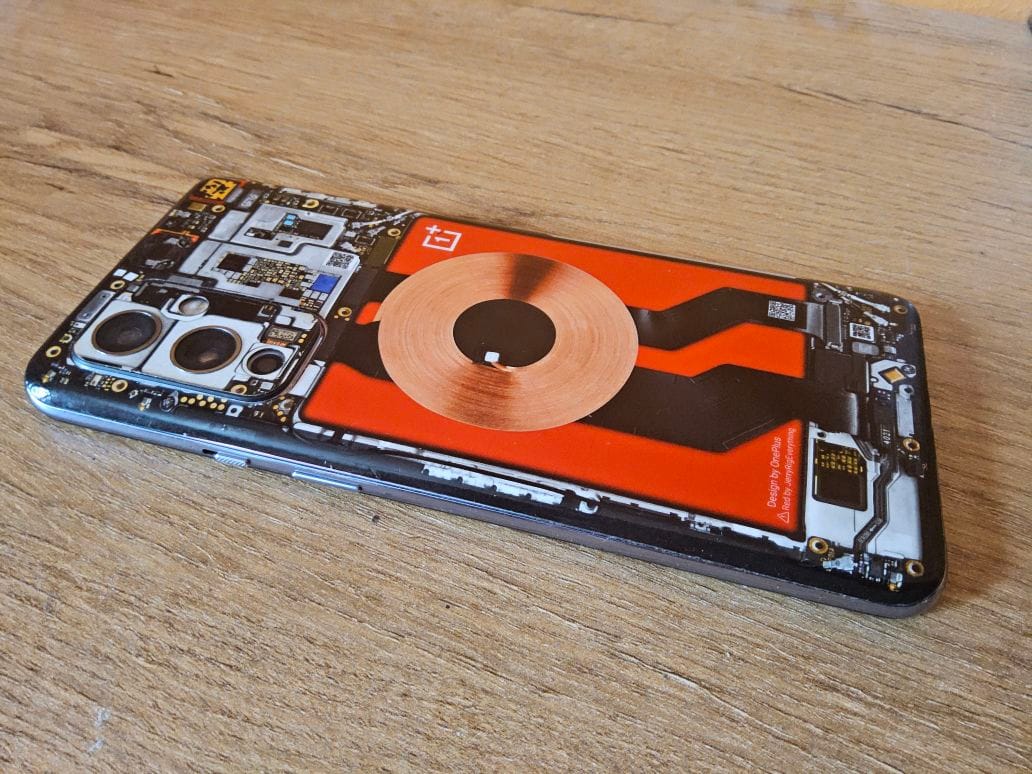

For years, I felt spiritually aligned with OnePlus and their motto “Never Settle.” It fits me — but it’s not the whole picture.

In 2026, I want to deliberately move toward owning my phone.

I also miss a proper low‑level hacking project — the kind where you might brick a device, debug it, and maybe bring it back from the dead.

So I’ve decided to port postmarketOS to my OnePlus 9.

I’ve given myself a one‑year frame. The plan is to use Halium and leverage the work of the LineageOS community.

In a recent post, I mentioned buying a “drawer phone.” One reason was this project. I won’t hack on a device that holds important data. Now I don’t have to.

How will it go?

We’ll see.

I’ll occasionally share milestones — or, as I like to call them, Roman Miles — as I reach them. Even if the project ends with a phone that barely boots, it will still have been a valuable learning and sovereignty exercise for me.

Happy hacking, 2026.