Many of us use the Latin script every day (A, B, C …). It’s used across many European languages — but it’s far from the only system. There’s Cyrillic, Greek, Arabic, Chinese characters, and others.

Now imagine a very common situation. You speak a European language, you’re comfortable with the Latin script, and you decide to learn Ukrainian or Russian. If you search online, you’ll most likely find courses taught in English.

What usually happens looks something like this:

You see a word written as привет. You hear it spoken and see it rewritten into Latin as privet. You then learn a language that may be closer to your native one — but you do so through English as a shared bridge. This is inefficient.

Transliteration — the act of mapping one script onto another — is always an approximation. And it’s heavily influenced by the target language.

Even languages that already use the Latin script bend it to fit their needs. Italian is a good example. Think about gli, as in famiglia. That combination represents a sound that Italian has — and many other languages don’t. Seeing it written helps a bit, but it doesn’t teach you how to produce the sound correctly.

So I started experimenting with a different approach: bypass transliteration entirely.

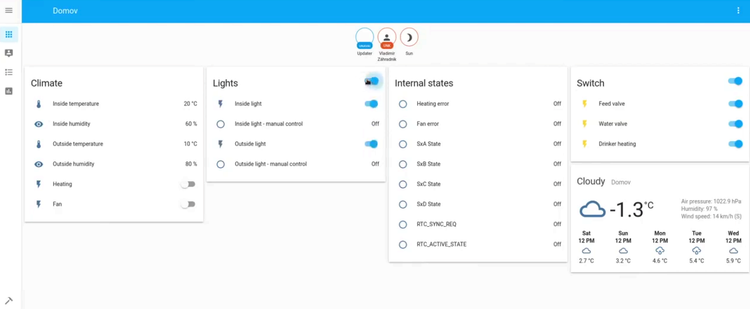

Instead of converting foreign scripts into Latin, I try to build a direct internal mapping — a kind of personal rainbow table — from the original glyphs to sounds I can already produce. At first, the mapping is crude. I connect each symbol to the closest sound available in my native language.

| Original Glyph | Approximated Glyph | Tongue / Mouth Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| л | l | Tongue touches the alveolar ridge behind the upper teeth | Close to English/Slovak l, but slightly softer |

| ль | ľ | Tongue presses closer to the hard palate, more palatalized | Similar to Slovak ľ; requires softening |

| р | r | Tongue vibrates against the alveolar ridge | Rolled r, stronger than English |

| и | y | Tongue pulled back, lips relaxed | Not English i; closer to Slovak y |

| і | i | Tongue high and forward, lips relaxed | Clean ee sound, like Italian i |

Note:

This table is not meant to be phonetically perfect. Its purpose is to create an initial, internal bridge from unfamiliar glyphs to producible sounds. Precision comes later through listening and correction.

Only later do I refine this internal mapping. Nuances come from active listening — real speakers, real cadence, real rhythm.

If I had to describe the shift, it feels similar to what happened when C++ moved away from being compiled through C. Once C++ had its own compiler, developers gained power. Classes no longer had to squeeze through an ill-fitting intermediary representation.

Removing that extra layer changed everything.

Scientia potentia est