There used to be a time before Dropbox.

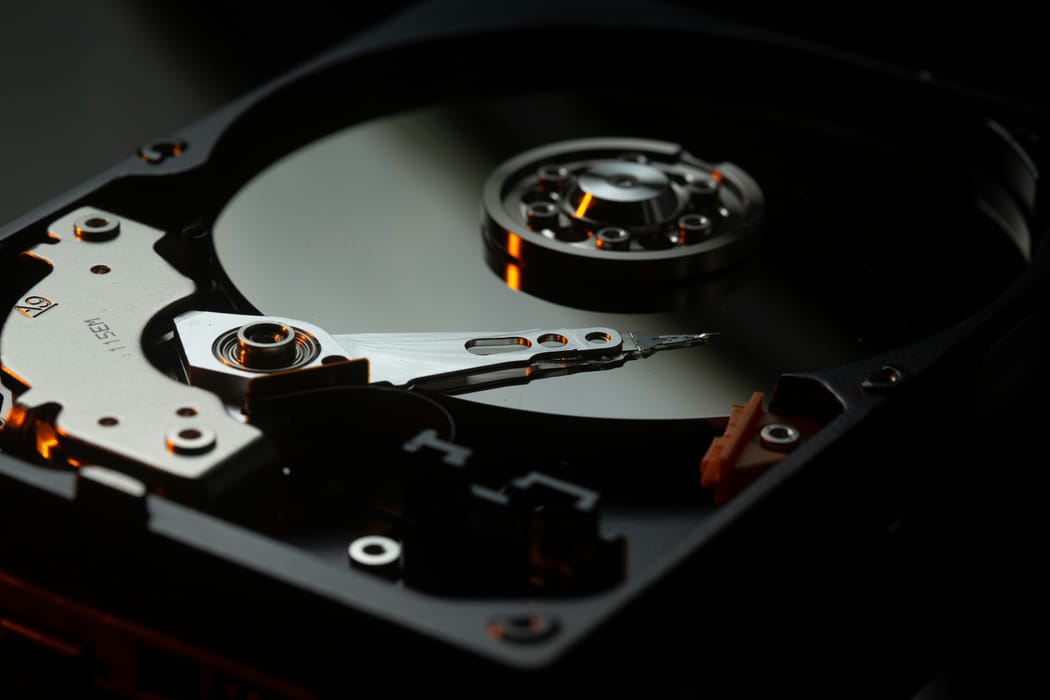

People — and companies — stored their precious data on physical hard drives. Backups were made on floppy disks, CDs, later DVDs, Blu‑Rays, and for the more serious cases, magnetic tapes.

Data loss was a real thing.

Individuals like my parents rarely cared about backups. They turned on the computer and assumed the data would still be there. They still do. And they still have no idea that data can silently rot.

Larger companies usually understood the risk. They had internal IT staff or external contractors responsible for backups, disaster recovery, and storage.

Responsibility was explicit.

And then came Dropbox

Dropbox was genuinely disruptive.

It wasn’t just an ever‑present USB stick. It promised something far more powerful: your data is safe in our cloud.

I’m not sure when the word cloud became mainstream, but it was around that era.

Note: In this article, Dropbox stands in for the entire category — Google Drive, OneDrive, iCloud, and similar services. Dropbox was first, so it represents the shift.

Another important Roman Mile came shortly after: widespread broadband internet — DSL, cable, and later fiber.

Together, these two developments fundamentally changed how we treat data.

From ownership to renting

Paying a small monthly fee to Dropbox was a no‑brainer.

Suddenly, responsibility was offloaded. If something broke, SLAs promised quick fixes. You didn’t need to pay contractors. You didn’t need to think about storage failures.

At the same time, faster internet and frictionless sync caused us to produce more data.

What used to be hundreds of megabytes became gigabytes. Then terabytes. And for some companies, far more.

How can I securely store 20 TB?

Backups were always annoying. They became hard once data volumes exploded.

Most people don’t truly understand gigabytes — let alone tebibytes. They just want their data to be saved.

Startups face a similar dynamic. Thousands are created every day. Speed matters more than infrastructure. Instead of building storage early, they subscribe to Google Workspace or Microsoft 365 and move on.

Convenient. Fast.

And often irreversible.

Convenience and the loss of ownership

We now live in the era of subscriptions.

Paying for storage that integrates perfectly with your operating system feels normal. Paying monthly feels harmless.

And for most people and companies, everything is fine.

Until it isn’t.

Laws change. Policies change. What’s allowed today may not be tomorrow. Large providers have the power to lock you out of your data — sometimes because of content decisions entirely unrelated to storage.

These cases are rare. I won’t pretend otherwise.

But when they happen, the people affected usually wish they had a local copy.

This article is not anti‑cloud. It’s an argument against unexamined dependence.

Reclaiming ownership

It took me years to deliberately cut my cloud dependency.

Part of it was emotional — paying Google a few euros because I crossed an arbitrary quota felt wrong. But the real reason was structural:

I wanted to own my data again.

The process was slow and intentional. You’d be surprised how many people pay for cloud storage simply because they’ve never audited their data. Once they cross 15 GB, paying less than the price of a coffee feels easier than understanding what’s actually stored.

My mother pays. Friends my age pay. Millions do.

Nobody taught them how to audit, delete, sort, or move data elsewhere.

Companies behave similarly. If they operate in the EU, GDPR compliance matters. If a vendor offers compliance and convenience, the decision is easy.

The risk appears later.

Lock‑in by design (not conspiracy)

A familiar example from startup life:

When you join Y Combinator’s Startup School, you’re often given cloud credits — typically AWS — so you can focus on building, not infrastructure.

This isn’t evil. It’s smart.

Once all your company data lives in one ecosystem and the credits expire, migration suddenly feels expensive and risky. So companies stay. Sometimes unhappily. Sometimes grinding their teeth over monthly invoices.

Meanwhile, people like David Heinemeier Hansson publicly show how much money companies can save by building and owning their infrastructure.

Different strategies. Different trade‑offs.

What “sovereign” actually means

When I talk about sovereign data handling, I don’t mean isolation or paranoia.

I mean:

- knowing where your data lives

- knowing how it’s backed up

- knowing how to leave if you must

That’s it.

The best time to design this is at the beginning, before you have hundreds of employees and deeply entrenched processes.

The later you pull the switch, the more painful it becomes.

I’m intentionally laying foundations before opening the gates.

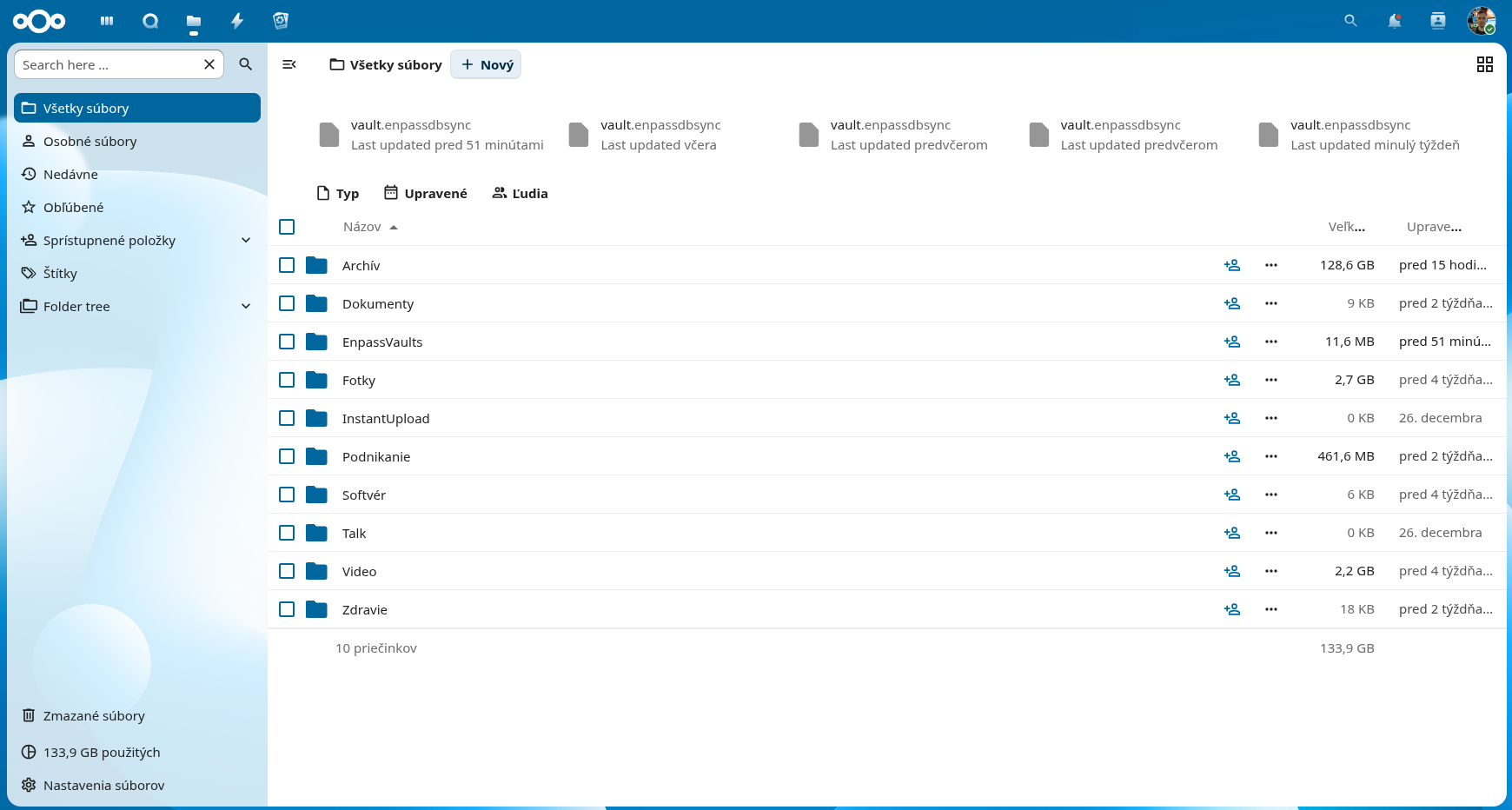

My solution in a nutshell — Nextcloud

About three years ago, I built my own cloud.

I wanted a Google Drive‑like experience, but I was willing to tolerate some friction. I chose Nextcloud.

Note: Like Dropbox earlier, Nextcloud represents a category. OwnCloud, OpenCloud, Synology, or similar setups can work just as well.

I chose Nextcloud because it’s open‑source, well‑reviewed, and actively developed with strong system integration.

I built two servers:

- one for personal data

- one for company data

Until recently, these were mixed. In December 2025, I deliberately separated them and formalized my backup strategy.

Because without planning, hardware failure can be catastrophic.

My infrastructure — high level

I’ll spare the hardware details. The principles matter more.

- Consumer‑grade hardware

- Software RAID 1 for primary storage

- Separate backup peers

- Manual and automatic replication

Home data is replicated manually once per month. Company data is replicated automatically to a geographically distant peer over a private VPN during off‑hours.

I also maintain offline backups on external drives — deliberately disconnected from power and network.

This protects against hardware failure, power surges, and ransomware.

What I’ve designed follows the 3‑2‑1 backup rule:

- three copies of data

- two different storage types

- one copy off‑site

Additionally, I’ve implemented geographical redundancy. If something happens at my primary office, my data survives hundreds of kilometers away.

Where this goes next

One day, I’d like a fully automated LTO tape system. Tapes are cheap and durable — up to 30 years when stored properly. The upfront costs are high, but the long‑term stability is unmatched.

Until then, I’ll keep formalizing the process and eventually delegate it to IT staff.

And what about my parents’ data?

Normally, I wouldn’t intervene.

But their computers hold accounting data relevant to my company — so I had to.

The solution was simple:

- Nextcloud accounts for both parents

- selective folder sync via the official desktop client

They don’t even know it’s there.

But now their data is automatically backed up and integrated into my broader strategy — with multiple redundant copies.

The system protects people who don’t want to think about systems.

Conclusion

Managing data is hard.

I don’t blame people or companies for outsourcing responsibility. But reclaiming ownership pays off if you’re building for decades rather than quick exits.

Sovereignty requires effort. But sustainability always does.

And if you’d like to discuss or consult on any part of this process, my DMs are open.

In data we trust.