How do polyglots hold five languages, ten languages — sometimes more — and stay sane? There is probably no definitive answer. We all have slightly different brains. Over the past days, I’ve been introspecting my own learning history to understand what was actually happening.

Even if this way of thinking doesn’t transfer one‑to‑one, I suspect parts of it can be adapted.

I learned German for at least eight years. Twenty years later, I can understand what people are saying, but my speaking is rusty. German was taught to me the standard school way: vocabulary drills, memorization, and correctness-first thinking.

English followed a very different path. I learned it mostly through immersion. I was never abroad, but I had to use the language — first as a networking engineer in my early jobs. What really tipped the balance later was media: thousands, maybe tens of thousands, of hours of exposure.

These two experiences left me with a very clear internal contrast.

English feels light, almost effortless. Speaking German, by comparison, feels like I need to invest a noticeable amount of energy just to produce a sentence.

That sensation is not unusual. When languages are learned in a highly structured, isolated way, they often end up stored in mental compartments. It’s also common for each foreign language to bring out a slightly different version of yourself.

If I had to describe this difference with a technical analogy, it would be this:

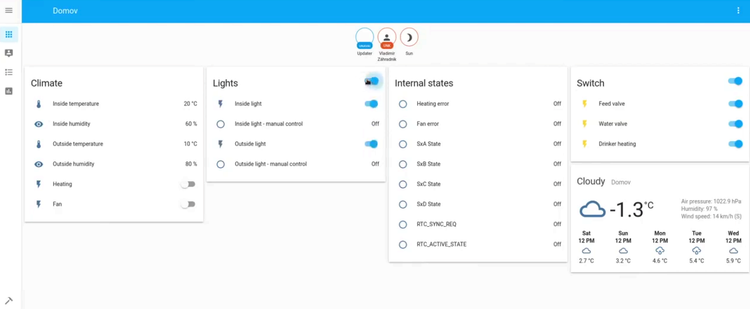

German runs in my head like a virtual machine. Booting into it costs time and energy.

English, on the other hand, feels like a lightweight container. Switching into it is almost instantaneous.

This talk touches a nearby layer of the same problem — immersion, early speaking, and why fluency emerges through use, not preparation.

The difference matters. English, as it lives in my head today, is sustainable — and more importantly, scalable. It doesn’t block me from adding other languages. It coexists with them.

This led me to a working hypothesis.

Rather than treating each language as a closed system, I try to understand languages as variations running on a shared cognitive baseline. The goal is not to think in a particular language, but to think through a system that can express itself in many languages.

In that sense, languages start to feel less like identities and more like interfaces to the world. Each language “container” holds a small set of specific rules — grammar, sounds, patterns — but shares the same underlying kernel.

When I learn something new, it often feels like this: I read about a language, sense its structure, extract its essence — and then try to emulate it.

What follows is a familiar feedback loop. I attempt to produce a sentence, notice where it breaks, adjust, and try again.

With languages living as lightweight containers instead of heavy virtual machines, switching becomes fast and natural. Just recently, I switched from German to English in the middle of a sentence without noticing it at first. The thinking stayed coherent — only the output changed.

That separation between thinking and speaking turns out to be crucial.

Describing deep internal cognitive processes is harder than it looks. But metaphors help — at least a little.

Il ne faut pas attendre d'être parfait pour commencer quelque chose de bien.

— Abbé Pierre