Foreword

This is the first article in a series where I’ll share my embedded war stories.

I’ve been thinking about writing this series for a long time, but it couldn’t be rushed. The projects I’m involved in are real, and premature leakage of information could have caused real damage.

If you enjoy embedded systems—or if you’re curious what actually happens inside a hardware startup—this series is for you.

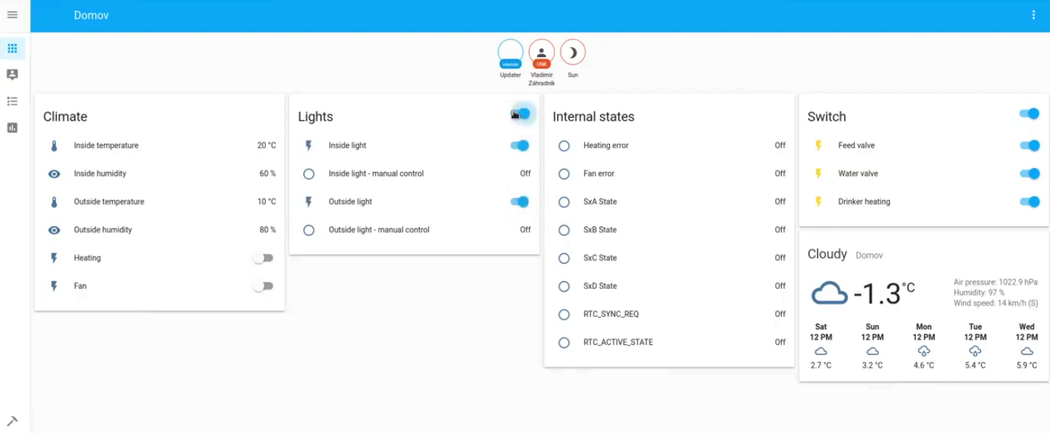

Early Home Assistant dashboard demo used during smart henhouse prototyping.

A New Customer

Back in 2020, I was collaborating primarily with my cousin. He’s a hardware engineer with deep real‑world experience; I covered the software side—and, as you’ll see, some of the systems thinking beyond it.

We were approached by a company that wanted a prototype of a smart henhouse. Their long‑term ambition was industrial automation for large facilities—henhouses for 700+ hens—but everyone has to start somewhere.

The prototype needed to demonstrate viability: hardware and software controlling lights, ventilation, water, and feeding, while collecting data such as egg production per hen.

The data was the real goldmine. Even anonymized, it opens the door to AI‑driven insights. Imagine thousands of henhouses feeding data into a system that detects anomalies and recommends changes in feed or environment.

We accepted the project. Later, we established a joint venture called Lutemi, where we became partners. While we haven’t entered the market yet, my part of the MVP work is already done.

The Prototype

A Proof of Concept is usually the first step in any hardware or software innovation. Unlike software, however, hardware prototypes cost real money.

Software development is relatively cheap and predictable. Investors care about the niche, the team, the roadmap, and when an MVP might arrive.

Hardware startups are a different beast. Mistakes cost not only time, but also physical components. There are fewer investors who understand hardware deeply, and fewer still who are willing to fund it.

Lutemi was self‑funded, which meant one thing: efficiency mattered.

We designed the prototype using standard, widely available components:

- Raspberry Pi 4

- Controllino MAXI (industrial‑grade Arduino)

- A mini rack

- Wiring

- A Merkur construction set

By that time, we had already delivered many projects using Raspberry Pi and Arduino boards. The technology was proven.

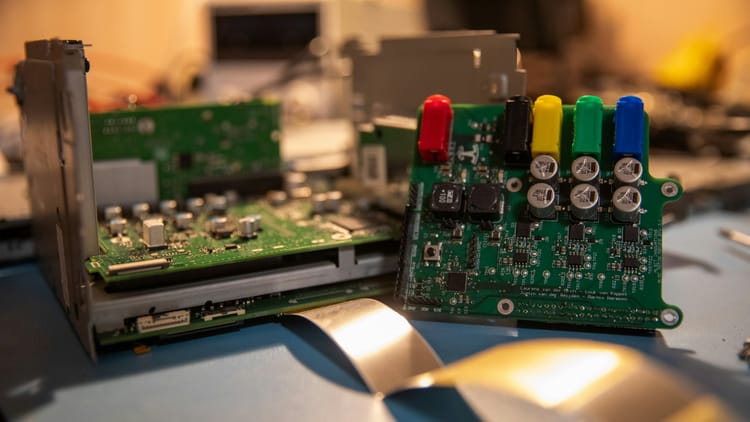

Arduino-controlled garage door prototype built using a Merkur construction set.

Why Not Just a Raspberry Pi?

A fair question. The Raspberry Pi has GPIO pins and can control devices—but only up to a point.

There were two key reasons we didn’t rely on it alone:

- Pin count — We needed far more I/O than the Pi could realistically provide.

- Real‑time constraints — Linux is not a real‑time operating system.

I had learned this lesson the hard way before. In a previous project, we sampled high‑frequency signals (motor sparks) to compute RPM. Linux scheduling introduced jitter that completely broke the measurements.

For tasks like that, you need a microcontroller.

So the architecture was clear:

- Arduino / Controllino — real‑time control and data acquisition

- Raspberry Pi — data collection, UI, visualization

Modbus Communication Protocol

The Raspberry Pi and the Arduino needed a shared language.

Physically, both devices were connected via an Ethernet switch. For the protocol, we chose Modbus—old, battle‑tested, extremely reliable, and still an industry standard.

Modbus Crash Course

Modbus is deceptively simple.

On many installations it runs on a shared bus (e.g., RS‑485). All devices see all messages, which is why every device has a unique ID.

To borrow from Les Misérables:

Javert (Master): “24601, is your LED light on?”

Jean Valjean (Slave): “No, not right now.”

Behind this simplicity is a register‑based model.

Modbus Register Types

| Register Type | Access | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Coils | Read / Write | Single‑bit outputs (e.g., turn light on/off) |

| Discrete Inputs | Read‑only | Single‑bit inputs (e.g., sensor states) |

| Input Registers | Read‑only | Arrays of uint16 values (e.g., temperatures) |

| Holding Registers | Read / Write | Arrays of uint16 values for configuration and data |

In a typical setup:

- One Modbus Master (Raspberry Pi / PC)

- Multiple Modbus Slaves (microcontrollers)

The master holds the full register map and polls devices periodically.

In our case, we polled once per second. That may sound frequent, but with just two devices, it was perfectly fine.

Mermaid Diagram — Javert Meets Valjean

graph LR

Javert[Modbus Master

Raspberry Pi] -->|Read Registers| Valjean[Slave 24601

Arduino]

Javert -->|Write Coils| Valjean

Valjean -->|Sensor Data| Javert

Home Assistant

I proposed using Home Assistant as the frontend.

At that time, I had never used it before. But I wanted hands‑on experience—and it turned out to be a great decision.

Home Assistant is built around integrations. Each integration lives in the same repository, but responsibility is decentralized. Once you’re listed as a maintainer, you’re notified about every pull request.

Modbus was already an existing integration—this became my bridge between Home Assistant and Arduino.

For the first time in my career, I was being paid to contribute to open source. A small but meaningful milestone for me.

Custom Home Assistant cards developed for monitoring and controlling henhouse systems.

Improving the Modbus Integration

When I joined, the Modbus integration worked—but barely. It only supported simple switches.

That’s fine for demos, but not for real users.

I implemented additional platforms:

- Climate (HVAC)

- Fan

- Light

This allowed us to model a proper UI instead of abusing switches for everything.

Later, another developer joined—Jan. One of the best collaborations I’ve had. He cared deeply about code quality and tests, and we were very much aligned.

Jan is likely still maintaining the Modbus integration today. I stepped away once we moved from prototype to dedicated device development.

If you’re curious, parts of my work are still visible in the Home Assistant codebase:

👉 https://github.com/home-assistant/core/tree/dev/homeassistant/components/modbus

Automations

Modbus gave us the raw plumbing—but a smart henhouse needs logic.

I used Home Assistant’s automation engine, writing YAML‑based automation scripts. Some were fairly complex, coordinating multiple sensors, time conditions, and fallback behaviors.

They’re archived now—more archaeology than production—but they did their job.

Delivery

We presented the prototype to the client. They loved it.

Shortly after, they proposed forming a joint venture. We accepted—trading short‑term stability for long‑term upside.

Unfortunately, COVID put development on hold not long after.

It took at least a year before discussions resumed.

And that’s where the next chapter begins:

From prototype to a real product.

Thanks for reading—and stay tuned.